Tobias Heiss (Universität Innsbruck)

A few years before the Austrian secondary education system underwent a structural reform in 1849, which established Ancient Greek as a mandatory subject, a Franciscan monk named Bern(h)ard Niedermühlbichler (1798–1850) already published two works of exemplary New Ancient Greek versification with a pedagogical goal in mind. As a teacher of classics in Hall in Tyrol he had first-hand experience with the obstacles that prevented his students – many of them to become clergymen later themselves – to achieve a better command of Latin and Greek during and after their schooling. Niedermühlbichler himself only taught fundamental grammar at the start of his career, before he became responsible for the so-called upper Humanitätsklassen, where poetry was read more extensively. Later, he was assigned the position of prefect within the school, before he became occupied with theological studies and instruction, namely canon law and church history, at the adjoined Franciscan monastery in Hall in Tyrol.

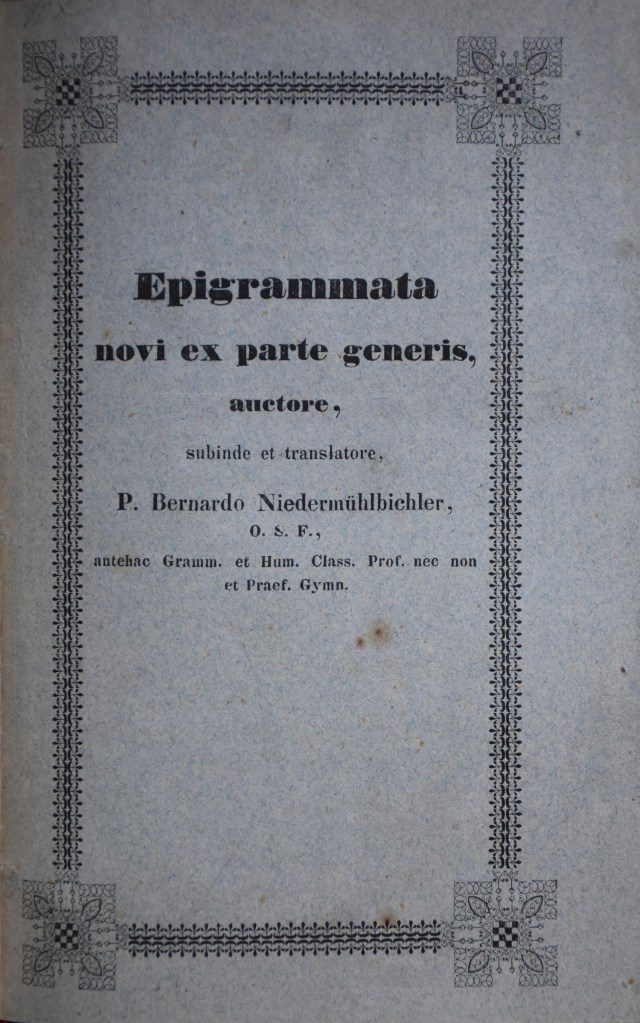

In 1844, Niedermühlbichler published a slim collection of playful Neo-Latin and Greek epigrams titled Epigrammata novi ex parte generis (Epigrams, partly of a new kind). The 225 Latin epigrams consist mostly of one- or two-liners and predominantly utilize the ambiguity of the language by means of wordplay – with an obvious example being anus in ep. 57 and 95. The twelve subsequent Greek epigrams, however, follow more traditional models. [Picture 2] Since not all readers were assumed to be fluent in poetical Greek and epigrams tend to be most effective if understood straightaway, the Greek pieces are accompanied by Latin prose translations and occasional explanatory endnotes. The poems’ themes and word choices are influenced by the epigrammatic tradition, as ep. 230 clearly shows, echoing an epigram by Palladas (Anth. Pal. 11.323):

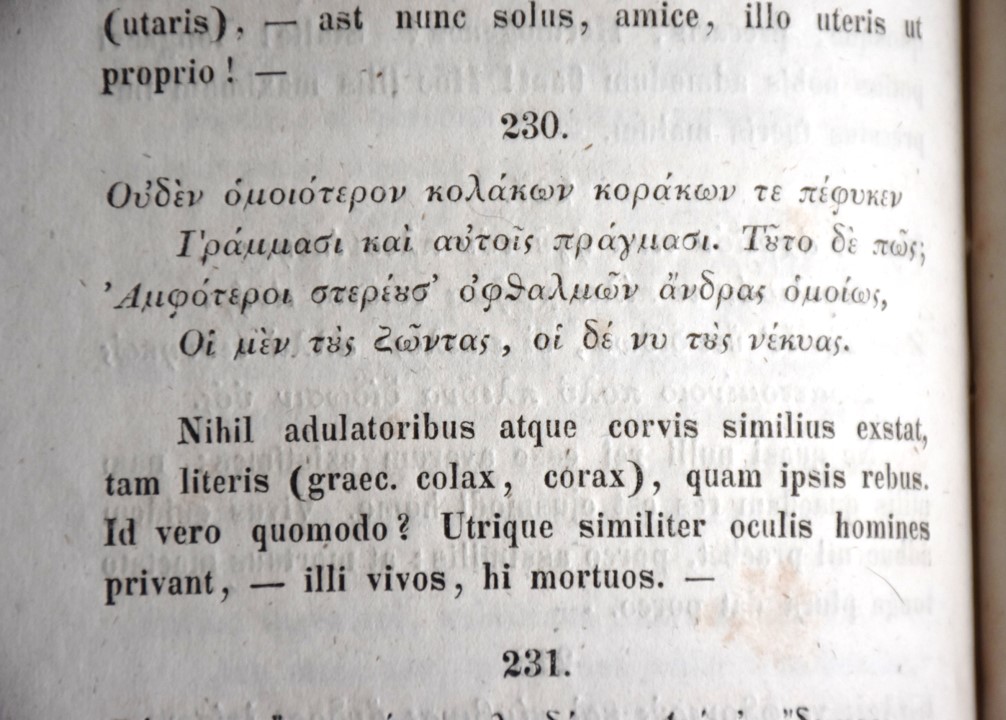

Οὐδὲν ὁμοιότερον κολάκων κοράκων τε πέφυκεν

γράμμασι καὶ αὐτοῖς πράγμασι. Τοῦτο δὲ πῶς;

Ἀμφότεροι στερέουσ᾿ ὀφθαλμῶν ἄνδρας ὁμοίως,

οἱ μὲν τοὺς ζῶντας, οἱ δέ νυ τοὺς νέκυας.

“There is nothing that has more similarity than flatterers and ravens,

both in their letters and essence. Why is that?

Both deprive men of their eyes in a similar way,

one the living, one the dead.”

The first words οὐδὲν ὁμοιότερον allude to other epigrams from the same book of the Anthologia (cf. 11.149.2, 11.151.2) and the closing antithesis ζῶντας–νέκυας is used in good epigrammatic fashion elsewhere in Niedermühlbichler’s collection (e.g. ep. 227).

Aside from efforts of refined imitatio, one also stumbles across instances of clever puns on the peculiarity of vernacular language. As Niedermühlbichler explains in his endnotes, the following epigram 234 was written on the occasion of a speech held by a friend, who happened to be a terrible speaker:

Ὡς σὲ νεωστί, παρὼν ἅμ᾿ ἔταις πλεόνεσσι, λέγοντα

ἤκουον, Ζῆν᾿ ἦν εὖ μάλα λισσόμενος,

οὖς ἐμὲ θεῖναι ὅλως ὅλον, – ὄφρα μένοιμ᾿ ἂν ἀκουστής

ῥᾷον, μηκέτ᾿ ἔχων, οἷς ῥὰ φύγοιμι ποσίν.

“As I heard you giving a speech not too long ago with countless friends present,

I prayed deeply to Zeus,

to make me all ears, so I could remain a listener

more easily, if I had no legs, with whom I could simply take flight.”

This depiction becomes even funnier, if we bear in mind the German idiom of being very attentive and eager to listen: ganz Ohr sein (to be all ears). Though lacking an equivalent in Greek, the joke is evident for the multilingual intended reader and adds an interesting comment on the German idiom, as if being literally all ears does not leave any choice but to listen. Witty allusions like these make the epigrams worthwhile and add some spice to their otherwise moralizing content. In his Praefatio, Niedermühlbichler explicitly defends his epigrams for lacking such gustus (p. 6) and notes the difficulty of even making sense at all in these types of epigrams that are solely based on homographs and polysemy. As the Greek epigrams strongly deviate in character from the Latin epigrams, it can be argued that they are written for a more erudite audience and are set out to please readers’ expectations of the epigrammatic genre.

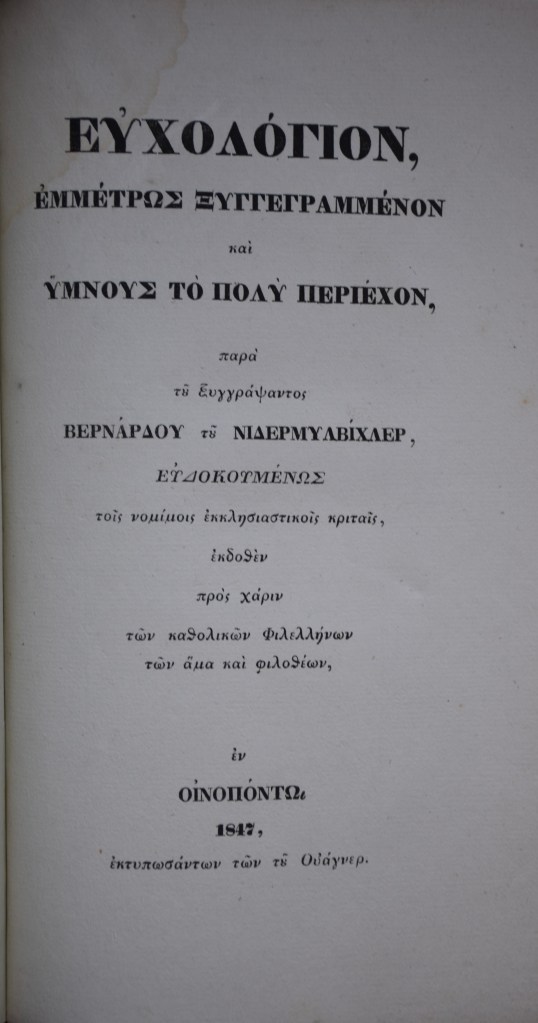

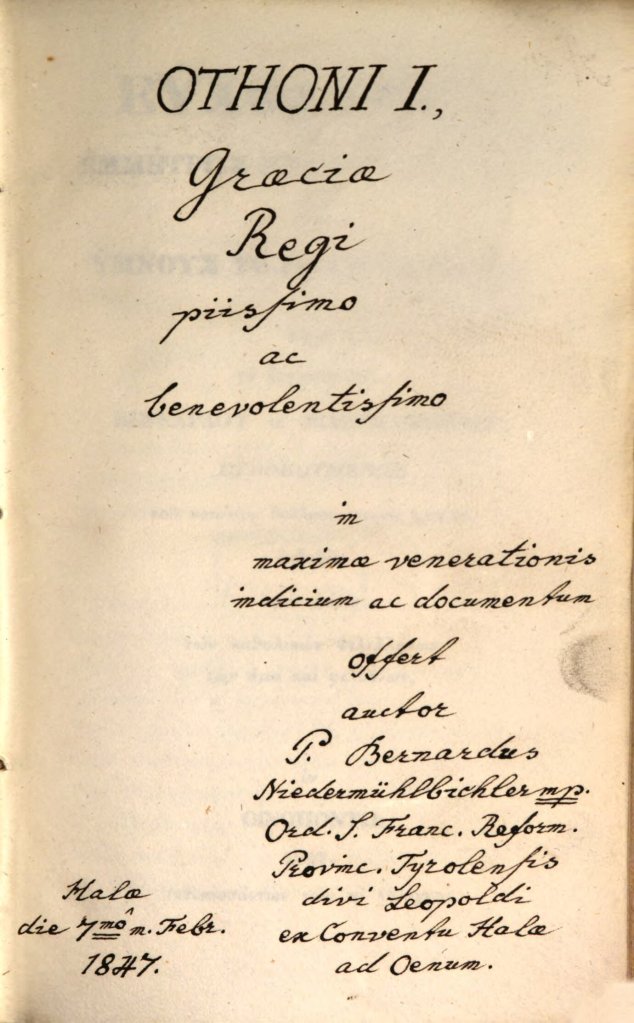

Niedermühlbichler’s command of Greek and his Hellenizing program become more evident in his tome Εὐχολόγιον (1847), a book of pious prayers in a variety of metres, written exclusively in Greek. The book opens with dedicatory hymns to Pope Gregory XVI, who passed away shortly before the publication in 1846, and king Ludwig I of Bavaria (1786–1868), whose son Otto, the first king of Greece (1815–1867), received a copy with a dedication by Niedermühlbichler on the fly leaf (Bavarian State Library Asc. 3432 f).

Niedermühlbichler expresses his views on the relation of Ancient Greek and German as part of a lengthy prologue (Πρόλογος ἀπολογητικός), defending the benefits of lifelong Greek learning even after school with the help of his book (p. XXXV):

[…] σώζοιτ᾿ ἂν […] ἐπιστήμη ἡ τῆς γλώττης, καὶ ταῦτα πολὺ τῶν ἄλλων περιούσης, τῶν ἐν τῇ Εὐρώπῃ πρεσβυτάτης, τῆς τῶν Ῥωμαίων ἐξ ἡμισείας γοῦν μητρός, αὐτῆς δὲ μάλιστα πασῶν ἐκμεμουσωμένης, λογικωτάτης τε καὶ σημαντικωτάτης ὑπαρχούσης, βραχείαις ταῖς συλλαβαῖς ὀλίγοις τε τοῖς ἔπεσι πολλὰ φραζούσης, καὶ ὅλως καλλίστης εἶναι ὡμολογημένης, ᾗτινι οὔτις ἂν τῶν νῦν ἐν ζῶσι γλωσσῶν κρατούσων περὶ τῆς ἀρετῆς καὶ πρωτείας ἐρίζοι, εἰ μὴ ἴσως ἡ τῶν Γερμανῶν διά τε ἰδίαν τινὰ δεινότητα ταύτης καὶ πολλὴν τὴν ὁμοιότητα πρὸς ἐκείνην καὶ ξυγγένειαν δέ τινὰ ἀναμφήριστον, ᾗ τὰ μὲν θυγάτηρ, τὰ δὲ καὶ ἀδελφὴ τῆς τῶν Ἑλλήνων γεγονυῖα γνωρίζεται.

“[In that way] the knowledge of the language could be preserved, which certainly surpasses all other languages, which is the oldest in all of Europe, which is seen at least half as the mother of Romans, which is the most melodious of all, and the most logical and expressive language, which can elaborate many things with short syllables and few words and which is altogether agreed upon to be the most beautiful, with which none of the languages among the living could compete in matter of excellence and rank, except perhaps the German language due to its particular exactness, the striking similarity with Greek and a certain undeniable kinship with it, which is why German is known sometimes as a daughter, sometimes as a sister, descended from the language of Greeks.”

This idea of a Greek-German kinship certainly appealed to the German royals and their aspirations in Greece at the time, who believed to be the true heirs of a noble civilization.

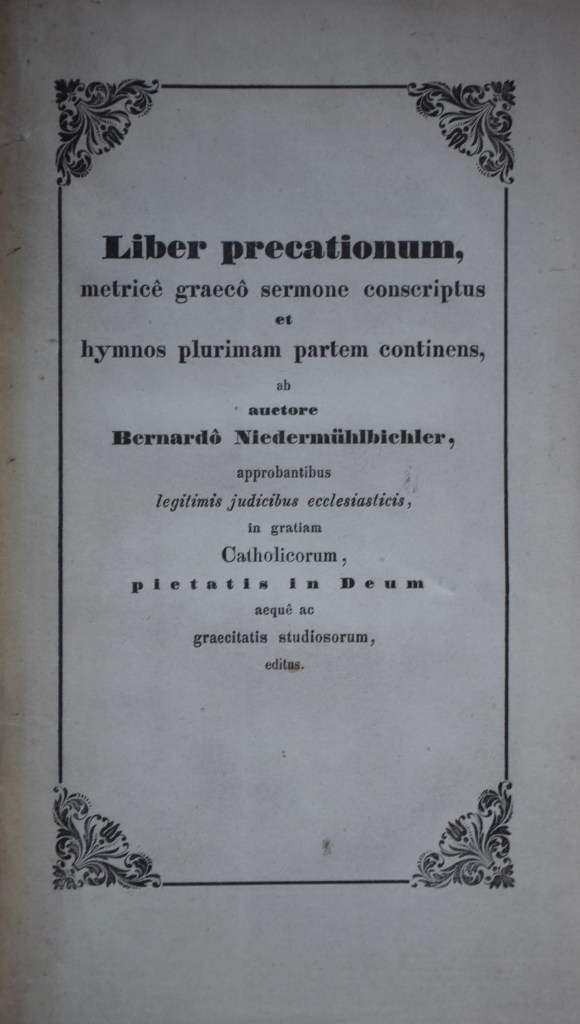

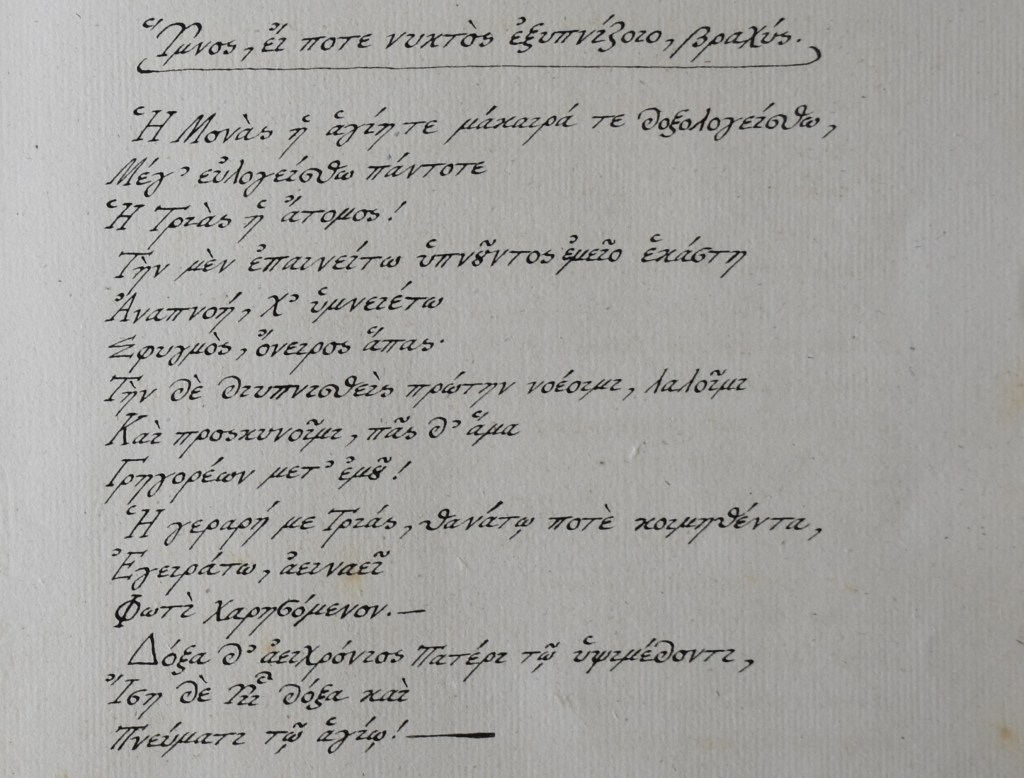

The twofold purpose of the Εὐχολόγιον is the benefit of prayer and the benefit of language learning (p. XXXIII). [Picture 6] After all, Niedermühlbichler was first and foremost a clergyman, only later to be followed by his occupation as a teacher of Greek. Because he was concerned with the place of Greek in modern times, he took it into his own hands to provide his students and other learners with daily prayers written in a language otherwise rarely used. Naturally, they should be studied repeatedly and at all sorts of different occasions, as titles like ῞Υμνος, εἴ ποτε ἐξυπνίζοιο, βραχύς (A short hymn, if you should wake up one night; p. 317) strongly suggest.

With his Εὐχολόγιον, Niedermühlbichler made an argument for Greek in terms of religious expression as well as a language of special interest for German speakers. This double aim meant that his second publication could speak to language learners, to religious leaders, and to political leaders at the same time. On the other hand, the Greek epigrams remain a hidden gem in his Epigrammata, a collection otherwise focused on the needs of Latin language learners. They may only pay off for the patient and persistent reader, a reader of the kind Niedermühlbichler distinctly wishes for at the end of his Praefatio (p. 8):

[…] Te, prudens ac benevole Lector! rogo, ut iam ad ipsa haec – a me sic dicta – epigrammata convertaris, eaque patienter legendo percurras, patienter et ipsum me feras auctorem; quem Tu si minus feres, ego Te feram, etiam plus aequo Catonem.

“I ask you, clever and kind reader, to direct your attention to just these epigrams, as I call them, already and to skim through them patiently, and, in addition to that, to put up with me, the author, in the same way. If you do not really put up with me, I shall put up with you in an even calmer manner than I do with Cato.”

Picture Captions

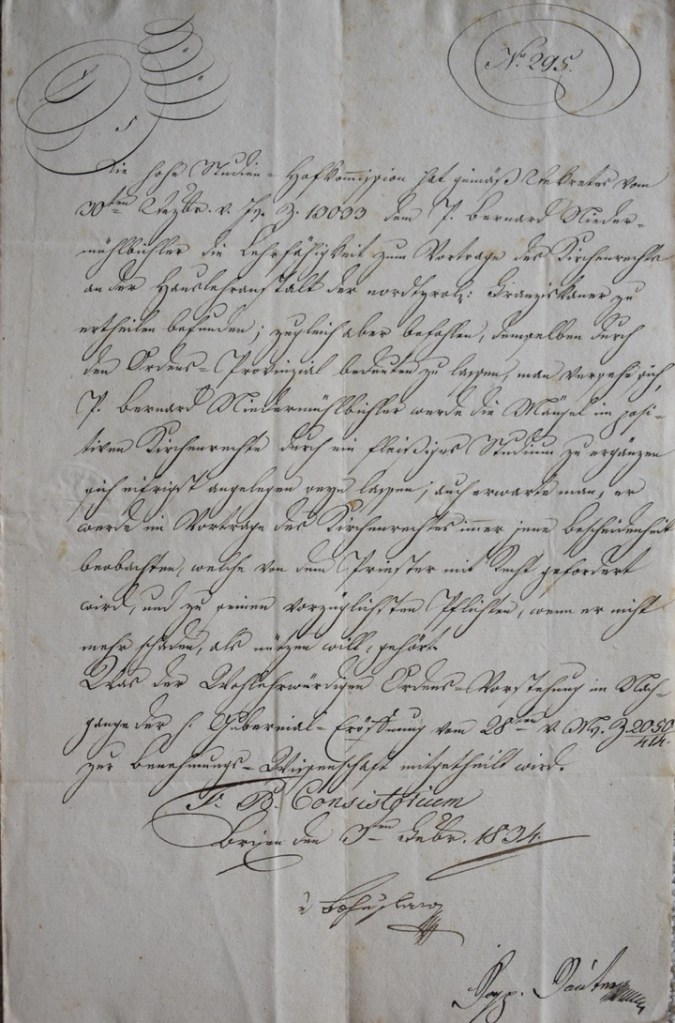

- Picture 1: Official permission to teach canon law from the diocese of Brixen in 1837.

Source: All pictures were taken by the author if not stated otherwise . - Picture 2: Front cover of Epigrammata novi ex parte generis (1844).

- Picture 3: Greek and Latin text of ep. 230.

- Picture 4: Front cover of the Εὐχολόγιον (1847) with the alternate Latin Title.

- Picture 5: Title page of the Εὐχολόγιον (1847).

- Picture 6: Dedication of the Εὐχολόγιον to Otto of Greece (1815–1867) on fly leaf. Source: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/view/bsb10265582 ?page=5 (last accessed: November 2024).

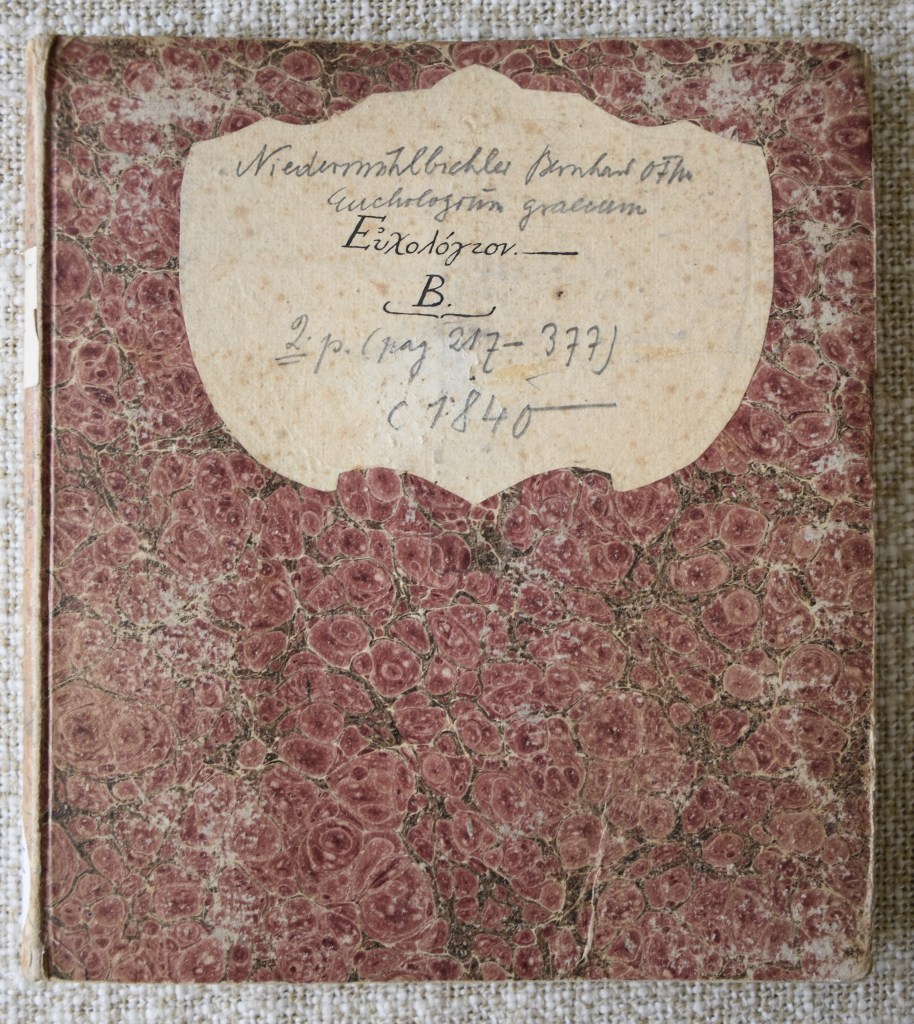

- Picture 7: Part of the Εὐχολόγιον has been preserved as a manuscript at the Franciscan monastery in Hall in Tyrol (Sig. MS I 401), corresponding to pages 175–326 in print.

- Picture 8: ῞Υμνος, εἴ ποτε ἐξυπνίζοιο, βραχύς in Niedermühlbichler’s handwriting.

Bibliography

- Barton, William M., Martin M. Bauer and Martin Korenjak. 2022. “Austria.”In The Hellenizing Muse: A European Anthology of Poetry in Ancient Greek from the Renaissance to the Present, edited by Filippomaria Pontani and Stefan Weise, 688–721. Trends in Classics–Pathways of Reception. Berlin & Boston: de Gruyter.

- Schaffenrath, Florian. 2012. “Von der Vertreibung der Jesuiten bis zur Revolution 1848: Dichtung.” In Tyrolis Latina: Geschichte der lateinischen Literatur in Tirol, Band II, edited by Martin Korenjak, Florian Schaffenrath, Lav Šubarić and Karlheinz Töchterle, 918–940. Wien, Köln & Weimar: Böhlau Verlag.

How to cite

Heiss, Tobias. 2024. “A Hellenic Voice from the Tyrolean Lowlands.” Hermes: Platform for Early Modern Hellenism (blog). 2 December 2024.

Deposit in Knowledge Commons: https://doi.org/10.17613/z6f78-cgc26.