Lev Shadrin (Universität Innsbruck)

<...> καὶ τὸ πνεῦμα, καίπερ μαλακὸν ὂν, ὤθησεν ἡμᾶς πρὸς Ἄνδρον.

Στεναγμοὶ τῶν ναυτῶν.

“<…> and the wind, as gentle as it was, pushed us towards the Andros island.

Sailors groan.”

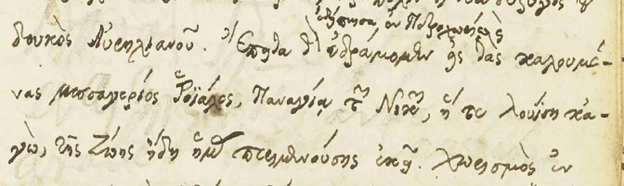

GSA 108/2922, Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv Weimar, f.51v

In 1837, Karl Benedikt Hase, a Franco-German Hellenist working in Paris, made a two-month long trip to Greece. His primary destination was Athens, where Hase planned to meet with his colleagues and attend lectures at the newly established University of Athens.

The only information about this trip comes from Hase’s private diary, which he has kept throughout his life, diligently recording daily events, meetings, dinners, and private affairs in an eclectic fusion of Ancient Greek interspersed with Modern Greek vocabulary and French transliterations.

Let’s take a glimpse at the passages describing Hase’s adventures across the Mediterranean and the Aegean seas and see what it was like to travel to Greece in the early 19th century.

Charting the course

The diary pages span the hot summer months of June and July 1837 and read very much like a travelogue, in contrast to the regular daily entries. The changes are evident in the content and narrative structure, vocabulary and syntax, and can even be noticed in Hase’s writing.

Taken out of his daily routine of editing manuscript catalogues for the Bibliothèque Royale, teaching Greek at the École Polytechnique, and moving around the same dozen places in Paris, Hase leaped at the opportunity to scrupulously record every step of the journey. Each travel day in the diary is bespeckled with toponyms, which have been diligently transcribed, transliterated or translated into Greek, supplied with necessary diacritics, and properly declined.

These named entities present the diary reader (and transcriber) with a collection of linguistic puzzles, some of which are quite easy to solve, e.g. Προβιγκία1 for the French region of Provence or Ἔλβα νῆσος for the island of Elba. In other cases, Hase refers to the ancient names of the cities, for instance, Μασσαλία for Marseille, Λούγδουνον for Lyon, or Νεαπόλης for Naples. Solving these toponymic riddles to correctly identify each location required consulting secondary sources, including 19th-century maps.

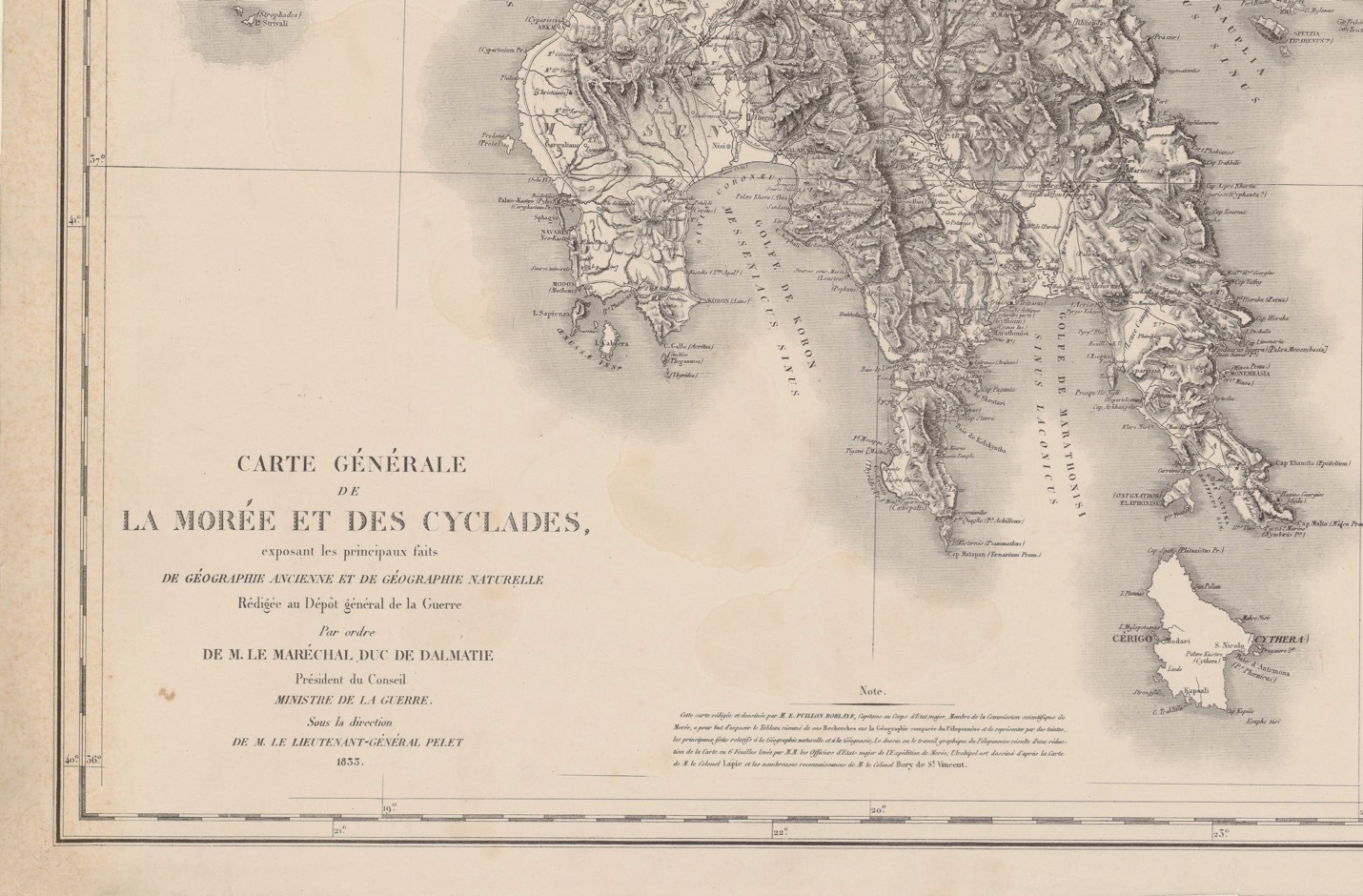

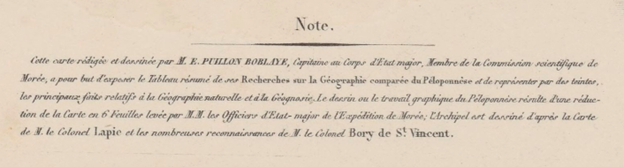

Hase is well known for his editorial contributions to, among other works, cartography charters – in previous diary entries he mentioned French cartographers Pierre Lapie and Émile Le Puillon de Boblaye, who had commissioned Hase to verify and append the Greek toponyms for their maps. On May 31, a couple of days before departing for Greece, Hase noted down a list of items packed away in his travel bag, which includes inter alia a map of the Cyclades by Boblaye.

“I have in my bag:

1. maps of the Rhône river

2. (maps) of the Peloponnese

3. a map of the Cyclades, by Boblaye”

An excerpt from the diary volume of 1837 (GSA 108/2922, f.46r)

One of Boblaye’s maps, La carte générale de la Morée et des Cyclades of 1833, is preserved at the Bibliothèque National de France. It features in detail the Peloponnese region along with the numerous Aegean islands and names of towns, villages, and islands. It is very likely that Hase had indeed packed a copy of this πίναξ τοῦ βωβλαῖε for the trip. Certain toponyms mentioned in the diary presented quite a challenge for identification at first. However, they align perfectly with the names of islands and cities featured on the map, which often contain both contemporary and ancient names:

| K.B. Hase, diary of 1837 | É. Boblaye, map of 1833 | Modern Greek name |

| ἡ νῆσος τοῦ Ἁγίου Γεωργίου τοῦ Δένδρου / Ἅγιος Γεώργιος δ’ Ἀρβώραν | St. Georges d’Arbora | Άγιος Γεώργιος Ύδρας |

| Γαϊδουρονῆσι | Gaïdero-Nisi (Patrocli Vallum) | Πάτροκλος (Γαϊδουρονήσι) |

| τὸ ἀκρωτήριον Μαλείαν | Cap Malio (Malea Prom.) | Ακρωτήριον Μαλέας |

| Ζέα | Zea (Ceos) | Κέα (Τζία, Κέως) |

| Θερμιά | Thermia (Cythnus) | Κύθνος |

After carefully transcribing the toponyms and identifying the names, I was able to put together a map of Hase’s travels. Since the road network of France has evolved quite significantly over the past 200 years, the lines connecting the nodes are quite arbitrary and serve as a general guide rather than an accurate route. The sea is even worse – there are no roads altogether, therefore I had to rely solely on the sequence of toponyms in the text, as well as occasional directions (e.g. “to the left we saw…”).

Coaches, boats, and ἀτμόπλοια

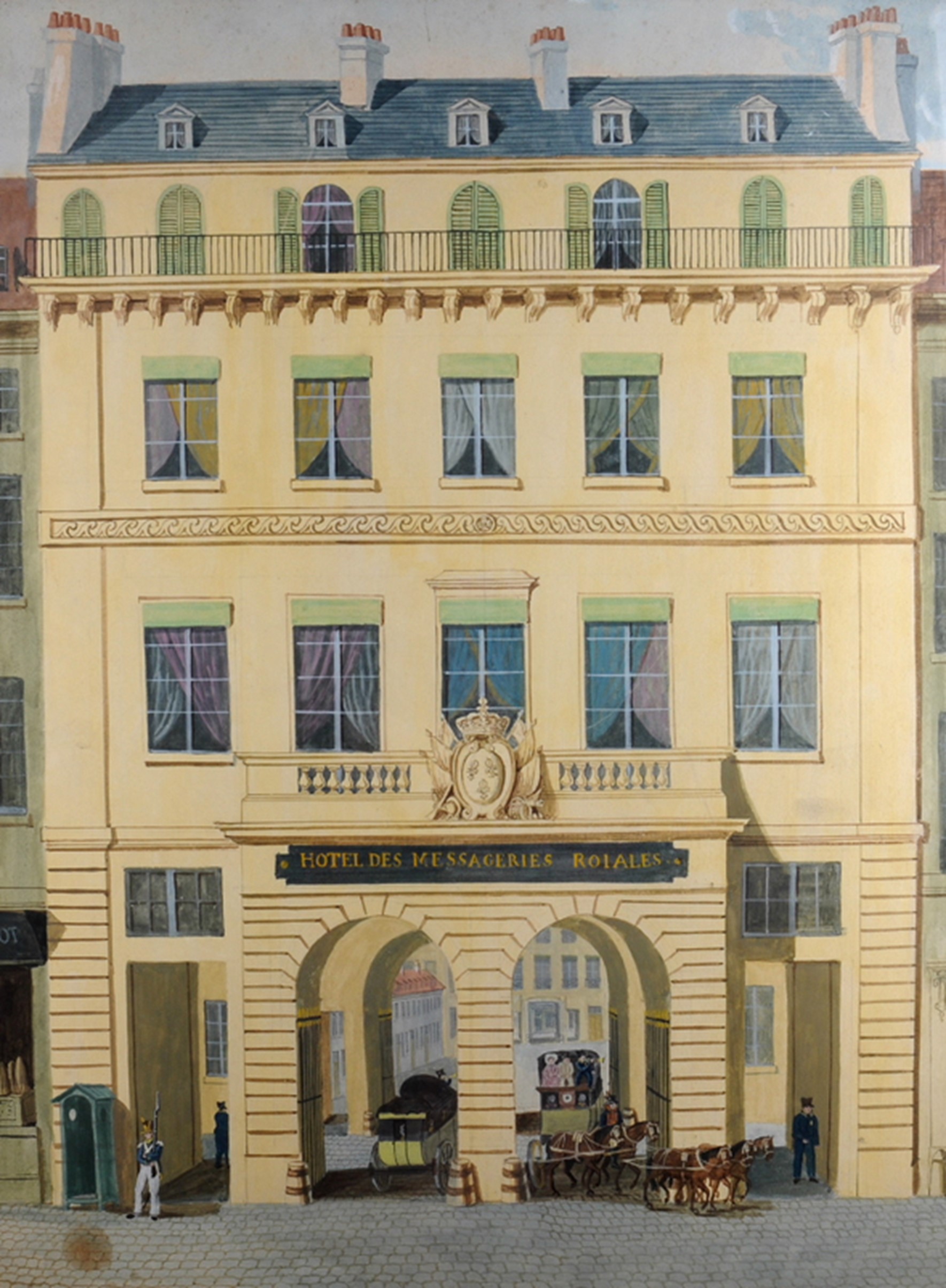

In today’s day and age, it is easy to overlook the troubles and perils of long-distance travels in the 19th century. Hase had to use several means of transportation, endure the tumultuous and unpredictable seas, and was even faced with a plague outbreak throughout his journey. He left Paris on June 4 in a stagecoach of Messageries Royales, a diligence company that provided postal and transportation services. After an emotional farewell with his maid Louise (χωρισμὸς ἐν κλαυθμῷ καὶ ξὺν ἡδίστῃ εὐδία, “departure in tears and in most pleasant weather”), Hase set off from the Hôtel des Messageries at rue Notre-Dame-des-Victoires (Παναγίᾳ τῶν Νικῶν).

<…> ἐδράμομεν εἰς τὰς καλουμένας Μεσσαγερίες Ῥοϊάλες, Παναγίᾳ τῶν Νικῶν <…>

<…> we rushed to the so-called Messageries Royales, at rue Notre-Dame-des-Victoires <…>

GSA 108/2922, f.47r

The stagecoach often traveled during the night (νυκτοπορία), but Hase was able to enjoy certain comforts, like breakfasts in hotels, spontaneous purchases (ἠγόρασα σειρῆτι ἔρυθρον καὶ φουλάρδιον, “I bought a red ribbon and a scarf”), and even an occasional coffee along the way (ἔπιον ἐκεῖ καφέ). In Lyon, Hase boarded a boat, which took him further south to Avignon, where he continued onwards to Marseille in a coupé carriage, μεταξὺ ἐμπόρου τινὸς ῥετιρὲ <…> καὶ νέου ἐμπόρου κωμμὶς βοιαγεῦρ, “between some retired merchant <…> and a young commis-voyageur.”

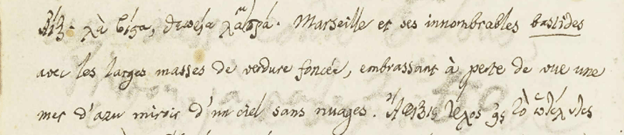

“Marseille et ses innombrables bastides avec les larges masses de verdure foncée, embrassant à perte de vue une mer d'azur miroir d'un ciel sans nuages.”

"Marseille and its countless bastides, with their broad masses of dark greenery, embracing as far as the eye can see an azure sea, mirror of a cloudless sky.”

GSA 108/2922, f.48v

Transliteration and code-switching are very frequent devices in Hase’s diary. Not only did he transcribe toponyms and neologisms into Greek, but on rare occasions he switched to French (like in the description of Marseille, shown in the picture above), German, or Latin to better convey his ideas.

In Marseille, Hase boarded a steamboat (the Modern Greek τὸ ἀτμόπλοιον almost looks out of place among all the classical Greek!), which carried him further into the Mediterranean – and to an inevitable stop on the island of Malta, which was at the time, unbeknownst to the travelers, ravaged by plague. This part of the journey, however, deserves a separate post!

The nine surviving volumes of Hase’s ‘Secret Diary’ form the core of the LAGOOS project, hosted at the University of Innsbruck and funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) [Y 1519-G], Grant DOI 10.55776/Y1519. The project, which I am very happy to be a part of, seeks to make the diary available to scholarship for the first time in a digital edition.

Follow our website for updates on the life of the 19th century scholar as we flip the diary pages! We also have a separate website for the digital edition, where the first volume (1825) has recently been published.

Footnotes

- All quotations from the diary are provided in a semi-diplomatic transcription, which maintains Hase’s orthography. ↩︎

Pictures

- The pictures of Hase’s diary are taken by the author from the manuscript Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv Weimar, GSA 108/2922.

- Pictures 1 and 2: details of Émile Le Puillon de Boblaye, Carte générale de la Morée et des Cyclades exposant les principaux faits de géographie ancienne et de géographie naturelle, 1833, paper, 49 x 81 cm. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Cartes et plans, GE DL 1839-74.

Source: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53035288h (last accessed: March 2025) - Picture 3: Paul Bruckmann, Diligence des messageries royales – Dessin, 1975, aquarelle, 49,9 x 64,9 cm. Paris, Musée de la Poste, 2017.35.26.

Source: https://collections.museedelaposte.fr/r/4d2f4dce-8bd3-4dc2-ab89-f15b3f042d59 (last accessed: March 2025) - Picture 4: Porche d’entrée de l’Hôtel des Messageries royales, rue Notre-Dame-des-Victoires, s.d. Paris, Musée de la Poste.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Porche_d%27entr%C3%A9e_de_l%27H%C3%B4tel_des_Messageries_royales.jpg (last accessed: March 2025)

How to cite

Shadrin, Lev. 2025. “Στεναγμοὶ τῶν ναυτῶν: Traveling from France to Greece in the 1830s.” Hermes: Platform for Early Modern Hellenism (blog). 1 April 2025.

Deposit in Knowledge Commons: https://doi.org/10.17613/9e6ap-x6r42