Domenico Graziano

(Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II – Universität Innsbruck)

In 1613, Jan Jacobszoon Paets, Leiden University’s printer (1603-1619), published a mature fruit of Daniel Heinsius’ (1580–1655) ‘Hellenizing Muse’: the Peplus Graecorum epigrammatum. Aside from an appendix of ἐρωτικά, which fills the final pages of the last gathering (removed in subsequent editions), the work is a collection of fifty-six Greek epigrams outlining a history of ancient philosophy through sketches of its protagonists; a combination of pseudo-Aristotle’s Peplus, Diogenes Laertius’ Vitae philosophorum, and – in its use of rare words and antipathy towards sophistry – Timon of Phlius’ Silloi, woven into an allusive tapestry by an author as learned as he was creative.

Heinsius was a leading figure of the late Renaissance: scholar and librarian, editor of ancient texts, literary theorist, and poeta trilinguis (Ancient Greek, Latin, and Dutch). His Greek poetry is renowned, but remained little explored in any depth, until Elisabeth Aydin’s preparations for critical edition of the Peplus with Les Belles Lettres began.

The care Heinsius took in producing such a refined work in Greek and the knowledge required to appreciate it spur questions about the Peplus’ genesis, aims, and intended audience. The first source of insights into these aspects of Heinsius’ poetic endeavour are its paratexts, which function as a δαίμων connecting the literary work to its intellectual and socio-cultural context. In this blogpost, I will focus on two paratextual elements, related respectively to the dedication and the epilogue of the collection.

The Peplus opens with a dedicatory letter in Latin addressed to the jurist, humanist, and diplomat Hugo Grotius (1583–1645). Discussing this letter as befits its interest for scholarship would require more than a few words, which I intend to do in a work I am developing as part of a forthcoming volume on early modern printed paratexts. Here, I wish only to draw attention to one remarkable aspect of Heinsius’ dedication to Grotius, namely that it is performed twice: firstly through the aforementioned Latin letter and secondly by a Greek liminal text, printed at the end of the collection. After the last poem devoted to an ancient philosopher, in fact, there is another Greek epigram, serving both as the final portrait in the gallery of wise men and as a carmen liminare, through which Heinsius consolidates the dedication at the beginning (p. 27): [The following transcriptions reflect the orthography and the use of diacritics found in the editio princeps, except for the accents in the title]

ΕΙΣ ΓPΩTION TΟN ΠΑΝΥ.

Γρωτιάδη περίπυστε, τετιμένε πᾶσι θεοῖσιν,Ἄρχων ἱστορίης, ἕρμα δικαιοσύνης,

Πᾶσαν τὴν σοφίην μεμυημένε, δέχνυσο τούσδε

Ἀνέρας, ἀρχαίης ἡγεμόνας σοφίης.

Εἰσὶ δὲ τεσσαράκοντα καὶ ἐννέα· τῶν κλέος αἰεὶ

Ἔσσεται, ἐκ Μουσῶν πάντῃ ἀειδόμενον.

Εἰ δὲ περισσοὶ ἔασι, τὶ τὸ πλέον; εἷς γὰρ ἀριθμὸν

Λείπων Γρωτιάδης ἄρτιον ἐκτελέσει.

“To the excellent Grotius

Illustrious Grotius, revered by all the gods,master of history, pillar of justice,

you who are initiated in all wisdom, accept these

men, leaders of the ancient wisdom.

There are forty-nine of them; their glory will last

forever, sung in every possible way by the Muses.

But if they are odd in number, what to add? One, Grotius,

leaving the number even, will bring it to its end.”

Thus, the Peplus begins and culminates with Grotius’ name. While the prose dedication letter in Latin stands clearly outside the core text, with this Greek epigram Heinsius blurs the line between text and paratext, having the dedicatee be both the addressee of the Peplus, paradigm of its ideal reader, and one of its characters – in a way, the most important. Heinsius uses the standard dedication at the beginning to provide the intellectual framework to understand his opus and associate it with the prestigious name of Grotius, but at the end he makes Grotius himself an integral part of the collection, using Greek poetry to consecrate him as not only an excellent scholar of philosophy, but a great philosopher himself, towards whom the gallery of wise men almost tends teleologically.

However, even though this poem literally puts the word ‘end’ (ἐκτελέσει) to the collection, the reader finds still another text before the erotic appendix. The epigram to Grotius is followed by a composition that serves as a coda and might provide a key to understanding Heinsius’ work. After a short prose introduction in Greek, which establishes the topic and expands the contents of the poem, the author writes (pp. 27–28):

Ἡ σοφίη θρεφθεῖσα παλαιγενέων ὑπʼ ἀοιδῶν,Οἷα παρ’ ἄχραντος μητέρι παρθενική,

Εἰς τοὺς λεσχομάχας μεταβαινομένη φύγεν ἄνδρας,

Τοὺς Μουσῶν φθορέας, τοὺς ἐρίδων προπόλους,

Ὡς δ’ ἴδε τὸν πώγωνα μέγαν Zήνωνος ἄνακτος,

Αὐτὸν δὲ μαλακῶς πὰρ πυρὶ κεκλιμένον,

Θέρμους ἀμφαφόωντα σοφῶς μάλα, καὶ τὸν ἀλήτην

Ἥρω βακτροφόραν, τὸν κύνα Διογένη,

Τόνθʼ Ἡράκλειτον μάλα δάκρυσιν ἀμφὶ ῥέοντα,

Τόντʼ Ἐπικούρειον νοῦν ἀτομοπλοκίδαν,

Οὐδὲν ἀνευροῦσα μεγάλη θεός, ἢ κενὸν ἀσκὸν

Δοξοσόφου μανίης, καὶ λογοδαιδαλίης,

Ἐψεῖν μὲν Zήνωνα φακὴν ὡς πρῶτον ἒασσε [sic pro ἐάσσε],

Τὸν κύνα δὲ ῥιγοῦν ὡς πάρος, ἠδ’ ὑλάειν,

Κλαίειν δʼ Ἡράκλειτον, ὅσον φίλον ἔπλετο θυμῷ,

Τὸν δʼ ἀτόμους τέμνειν τὰς ἀπεραντολόγους·

Αὐτὴ δʼ ἐς Μουσέων γλυκερὸν πάλιν ἤλυθε κόλπον

φεύγουσα, προτέρην ὧν ἔχε τὴν κομιδήν.

“Wisdom, nurtured by the ancient bards,like an immaculate maiden by a mother,

ran away, turning to quarreling idlers,

the corrupters of the Muses, the ministers of conflicts.

But as she saw the great beard of lord Zeno,

and himself laying languidly reclined by the fire,

filling his hand with lupin beans – wisely indeed! –, and the wandering

stick-bearing hero, the dog Diogenes,

and Heraclitus overflowing with tears,

and the Epicurean mind weaving atoms,

the great goddess, who found nothing but an empty sack

of pretentious madness and word-craft,

she let Zeno stew his lentil-soup as before,

she then let the dog shiver as before and bark,

she let Heraclitus weep to his heart’s content,

and she let him cut the atoms, endless in their discourse (?);

but she returned fleeing to the sweet embrace of the Muses,

from them she got the care she used to receive”.

Leaving aside a broader discussion of Heinsius’ poetics and critical positions, I wish to highlight some suggestions raised by the epilogue of the Peplus, including both the epigram and its prose preamble. Here, Heinsius outlines the ‘misfortunes of wisdom’, which he situates in the shift from the prisca sapientia of poet-philosophers (e.g. Orpheus, Homer, Empedocles) to the mundane rhetoric of the ‘sophists’. As in Timon’s Σίλλοι, the thinkers labeled as sophists, devoted to empty quarrels, are leaders of philosophical schools promoting conflicting ideas, which includes the stoic Zeno, the cynic Diogenes, Heraclitus, and Epicurus. On the other hand, Heinsius’ sarcasm seems to spare Plato and Aristotle, who are not among those who scare wisdom away and whose doctrines he may have regarded, in line with Renaissance Neo-Platonism, as intrinsically harmonious and compatible with the divine truth expressed by poets.

In an age heavily influenced by the debate surrounding Aristotle’s Poetics (which Heinsius himself had edited in 1611, two years before the first edition of the Peplus), where poetry and philosophy are considered separate fields, the Peplus seems to suggest that true wisdom is rooted in poetic inspiration, and as such it can be attained exclusively through a poetic practice of thought. In this case, Heinsius is not merely advocating a return to such philosophy, but moreover enacting it himself, since in the dedicatory letter he regards doxography and history of thought as branches of philosophia themselves. Therefore, the eventual return of Σοφίη to the embrace of the Muses that marks the end of the Peplus would be a metaphor for Heinsius’ own work, which presents itself as more than an erudite endeavour: it fulfills the reconciliation of poetry and philosophy, established in New Ancient Greek verse.

Figures

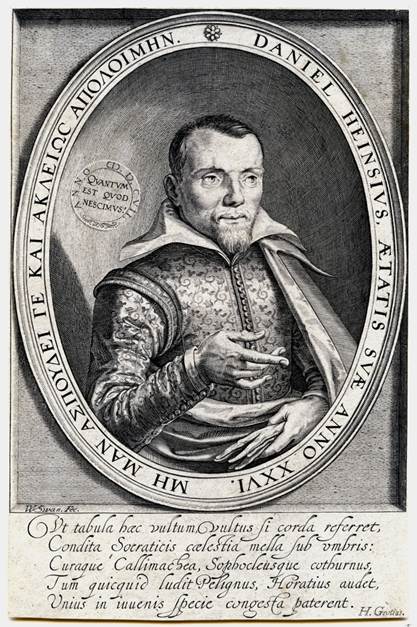

- figure 1. Willem Swanenburgh, Portrait of Daniel Heinsius at the age of twenty-six, c. 1607, engraving, ink on paper, Universitaire Bibliotheken Leiden. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_Daniel_Heinsius,_librarian_and_professor_of_Poetry,_Greek_and_History_at_Leiden_University,_at_the_age_of_26_PK-1884-P-13.tiff.

- figure 2. Crispijn van de Passe, Portrait of Hugo Grotius at the age of fifty-three, 1636, engraving, ink on paper, Collectie van prenten van C.G. Voorhelm Schneevoogt te Haarlem. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portret_van_de_Nederlandse_rechtsgeleerde_en_schrijver_Hugo_de_Groot,_op_53-jarige_leeftijd._In_het_randschrift_van_de_omlijsting_de_naam_en_functie_van_de_geportretteerde_in_het_Latijn._In_,_NL-HlmNHA_1477_53011410.JPG

- figure 3. Raffaello Sanzio, Allegory of Poetry, 1509–1511, fresco, 180 x 180 cm, Città del Vaticano, Stanza della Segnatura. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Volta_della_stanza_della_segnatura_03_poesia.jpg

- figure 4. Raffaello Sanzio, Allegory of Philosophy, 1508, fresco, 180 x 180 cm, Città del Vaticano, Stanza della Segnatura. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Volta_della_stanza_della_segnatura_02,_filosofia.jpg

Sources

- Heinsius, D. (1613), Peplus Graecorum epigrammatum, In quo omnes celebriores Graeciae philosophi, encomia eorum, vita, et opiniones recensentur, aut exponuntur, Jan Paets Jacobszoon, apud Lodewijk I Elzevier, Leiden (USTC 1015759).

References

- Aydin, E. (2018), Le “Peplus Graecorum Epigrammatum” de Daniel Heinsius, une adaptation de Diogène Laërce à la Renaissance, in «Neulateinisches Jahrbuch» 20, pp. 29-55.

- Becker-Cantarino, B. (1978), Daniel Heinsius, Boston.

- Golla, K. (2008), Daniel Heinsius’ Epigramma auf Hesiod, in Daniel Heinsius: Klassischer Philologe und Poet, edd. Lefèvre, E. – Schäfer, E., Tübingen, pp. 31–55.

- Kern, E. (1949), The Influence of Heinsius and Vossius upon French Dramatic Theory, Baltimore.

- Lamers, H. – Van Rooy, R. (2022a), “Graecia Belgica”: Writing Ancient Greek in the Early Modern Low Countries, in «Classical Receptions Journal» 14, 4 (2022), pp. 435-462.

- Lamers, H. – Van Rooy, R. (2022b), The Low Countries, in The Hellenizing Muse: A European Anthology of Poetry in Ancient Greek from the Renaissance to the Present, edd. Pontani, F. – Weise, S., Berlin, pp. 249-251; 253-254.

- Meter, J. H. (1984), The Literary Theories of Daniel Heinsius: A Study of the Development and Background of His Views on Literary Theory and Criticism During the Period from 1602 to 1612, Assen.

- Sellin, P. R. (1968), Daniel Heinsius and Stuart England, Oxford.

- Wels, V. (2013), Contempt for Commentators: Transformation of the Commentary Tradition in Daniel Heinsius’ “Constitutio tragoediae”, in Neo-Latin Commentaries and the Management of Knowledge in the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period (1400-1700), edd. Enenkel, K. A. E. – Nellen, H., Leuven, pp. 325-346.

How to cite

Graziano, Domenico. 2025. “On the Hem of Daniel Heinsius’ ‘Peplus Graecorum epigrammatum’: Poetry, Philosophy, and Paratexts in New Ancient Greek.” Hermes: Platform for Early Modern Hellenism (blog). 1 June 2025.

Deposit in Knowledge Commons: https://doi.org/10.17613/76npd-xfn77