Dries Nijs (KU Leuven)

Leiden University library houses an extensive collection of printed disputationes. These broadsheets and pamphlets present the theses that university students — the respondentes — defended against opponentes, under the supervision of a professor acting as praeses. This corpus extends from shortly after the founding of Leiden University (1575) into the 20th century, filling several bookcases in the Special Collections.1 Next to the theses, primarily in Latin, these ephemeral academic prints contain liminary dedications and congratulatory poems in a range of vernacular and learned languages. A medical disputation from 1686 features one of the most remarkable felicitations: a New Ancient Greek poem by an unknown woman, Margareta Ripen.

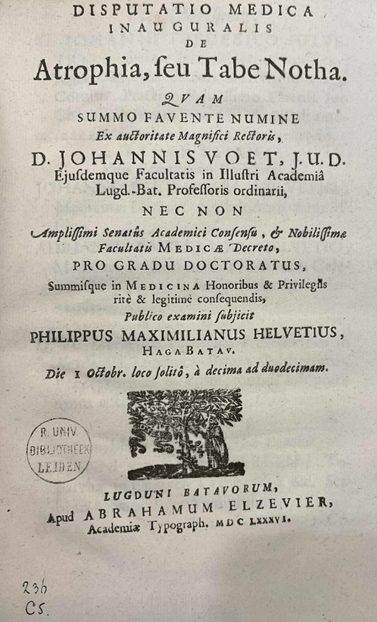

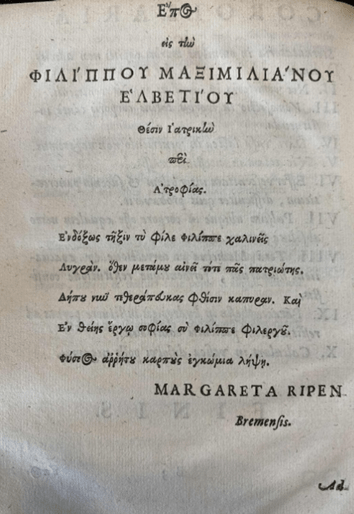

The professors, students and acquaintances attending the medical disputation of Philippus Maximilianus Helvetius on 1 October 1686 in Leiden, must have paused in surprise when, leafing through the pamphlet printed for the occasion by Elsevier, they encountered at the end—among the usual congratulations in Latin and Dutch—a New Ancient Greek poem written by a woman.2 The majority of the audience, no doubt, could not read the Greek text, let alone understand its meaning. Yet we can imagine that they were struck by the learned and exotic language in which it was written—and even more so by the signature, which identifies a female author: Margareta Ripen of Bremen. Poetry in New Ancient Greek is relatively rare, especially in the final decades of the seventeenth century. The production of Greek gratulatory verses for disputations peaked in Leiden around 1600, but soon receded to the margins, where it seems to have stagnated as a peripheral phenomenon throughout the seventeenth century. Of all 1708 poems in Leiden disputations that I have been able to trace up to the year 1700, only 42 (2,46%) are in Greek, with their proportion decreasing in the last quarter of the century compared to Latin and vernacular verse. Within this context, Margareta Ripen’s poem is all the more exceptional: it is not only the sole Greek composition among the forty-five carmina gratulatoria from 1686, but also the only New Ancient Greek poem written by a woman, at least within the corpus of the early modern Low Countries, which is currently being mapped by the HellBel project at KU Leuven.

Little is known about this Margareta Ri(jp)pen or her connection to Philippus Maximilianus. Her name appears at the end of three other liminaria in Latin: two poems for Petrus Rabus’ translations of Herodian3 and Ovid,4 and a dedication to his son Guilielmus in a schoolbook of fables.5 The latter signature includes an additional surname: Margareta Harwich Ripen Bremensis. This points us to her husband, Maternus Harwich, teacher at the Latin school of Rotterdam and author of a bilingual schoolbook on rhetoric.6 The couple had two children, one of whom—a son named Sophronius—was baptized in Rotterdam on 11 June 1682.7 Rotterdam seems to be the only place to which Margareta can be linked, as no trace of her self-proclaimed Bremen origins is known. She appears to have died young and was buried in that same city on 27 December 1694, leaving her children still underage.8

Ἔπος9

εἰς τὴν

Φιλίππου Μαξιμιλιανοῦ

Ἑλβετίου

θέσιν ἰατρικὴν

περὶ

Ἀτροφίας

Ἐνδόξως τῆξιν τὺ φίλε Φίλιππε χαλινοῖς

λυγράν, ὅθεν μετά μου αἰνεῖ τότε πᾶς πατριώτης.

Δήπου νῦν τεθεράπευκας φθίσιν καπυρὰν. Καὶ

ἐν θείης ἔργῳ σοφίας σὺ Φίλιππε φιλεργοῦ.

Φύσεος ἀρρήτου καρποὺς ἐγκώμια λήψῃ.

Margareta Ripen

Bremensis

Poem

for

Philippus Maximilianus

Helvetius’

medical thesis

on

Atrophy

Gloriously, dear Philippus, you restrain the

mournful tuberculosis, for which together

with me, every compatriot praises you. Surely

now you have cured the drying phtisis.10 And

be industrious, Philippus, in this work of

divine wisdom. As praise, you will reap

the fruits of ineffable nature.

Margareta Ripen

of Bremen

Although the author of these verses is exceptional, their content and poetic quality are not. Like other New Ancient Greek occasional poetry of this period, the text shows several errors against the Greek, its accentuation and printing, listed in the footnotes below. The dactylic hexameter used here is one of most common meters for this kind of poetry, likely chosen for its solemn tone as well as its relative accessibility and straightforwardness. The content is like that of most gratulatory poems in disputations: somewhat superficial flattery, generic and derivative. Typical features are the wordplay on the respondent’s name (φίλε Φίλιππε, Φίλιππε φιλεργοῦ), the repeated reference to the disputation’s subject (τῆξιν, φθίσιν), the intertextual engagement with (late) antique or early Christian sources, usually only superficial (Φύσεος ἀρρήτου καρποὺς11), and the excessive praise of the student’s achievement, which is said to have a revolutionary impact on society as a whole and possess a divine quality. In this way, even though it was written by a woman, this poem is a textbook example of the Greek gratulatory verses found in early modern disputations. Their significance lies not in what they say, nor in how well they say it, but simply in the language they use.

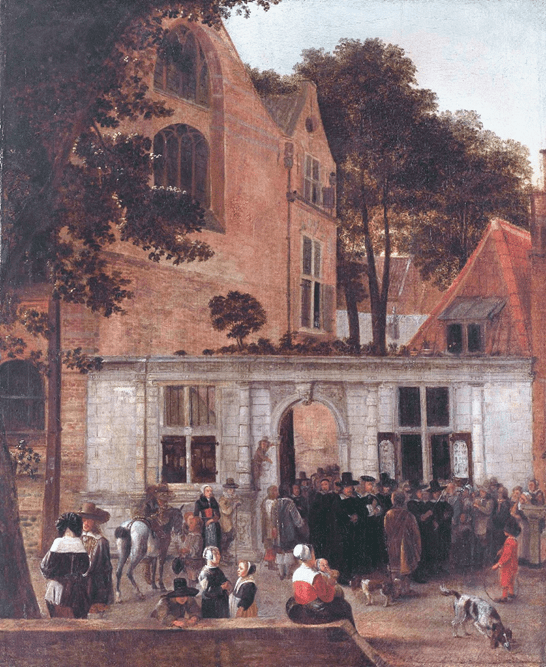

The practice of including gratulatory poems in disputations served as a form of self-presentation. Through these poems, students and authors could shape their imago, show off their learned connections and define their position in the intellectual network of Leiden University. The choice of writing or including Greek texts was relatively exceptional, offering a way to stand out further and distinguish oneself among the more conventional Latin and vernacular felicitations. By choosing Greek, authors and students demonstrated that they belong to an in-group of Hellenists who possess an extraordinary kind of cultural capital:12 knowledge of a learned language and literature incomprehensible for the broader public. In this context of impressing peers and standing out among them, a Greek poem written by a woman is of course especially striking. We can only speculate about the audience’s reaction to this specific poem, but since learned women were already admired and regarded as extraordinary at the time,13 it is easy to imagine that this composition made an especially powerful impression, lending Philippus Maximilianus and his disputation a distinctly erudite and exceptional aura.

Footnotes

- My research on this collection was made possible by a Brill Fellowship at the Scaliger Institute in Leiden in the summer of 2025, for which I express my gratitude.

- Philippus Maximilianus Helvetius (1665–1708), the third son of Johann Friedrich Schweitzer, settled as a city physician in Middelburg after completing his studies. In 1704, he was appointed military doctor in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen, and later became lecturer in anatomy in Rotterdam. In addition to this disputation on atrophy, he wrote a handbook for midwives entitled Teel-thuin van ’t menschelijk geslagt (Leiden, Frederik Haaring, 1698). Cf. also Molhuysen, P.C. & Blok, P.J. (1914) Helvetius, Philippus Maximiliaan. In Nieuw Nederlandsch biografisch woordenboek (Deel 3, p. 573); A. W. Sijthoff. and Van Heiningen, T. W. (2014) La dynastie des Helvétius. Histoire des Sciences Médicales, 68(4), 447–456.

- Herodianus’ Acht boeken Der Roomsche Geschiedenissen. Rotterdam, Isaak Naeranus, 1683.

- Publii Ovidii Nasonis Metamorphoseωn Libri XV. Rotterdam, Reinier Leers, 1686. With multiple reprints.

- Compendium Fabularum, quae serviunt ad intelligentiam Virgilii, Ovidii, Senecae, Homeri, Euripidis et aliorum in usum scholarum. Rotterdam, Petrus vander Slaart, 1695. Reprinted in 1705.

- Orator Belgico-Latinus, demonstrans quo laboris compendio eloquentiæ candidatus ad oratoriam pervenire possit. Amsterdam, Jakob van Royen, 1701. The work was reprinted in 1729 and is in fact a translation of the first chapter of Christian Weise’s Politischer Redner (Leipzig 1679). Cf. also Meerhoff, K. (2020) Le persiflage enseigné en classe de rhétorique (L’Orator Belgico-Latinus, 1701). In C. Deloince-Louette & C. Noille (ed.), Expériences rhétoriques. Mélanges offerts au professeur Francis Goyet, pp. 55–68. Classiques Garnier.

- Rotterdam City Archives: https://hdl.handle.net/21.12133/19932BEACB6546FE9B142335776CAC53

- Rotterdam City Archives: https://hdl.handle.net/21.12133/03CFE518D3104E66873E33219B8D7E4F

- Text: Disputatio medica inauguralis de atrophia, seu tabe notha quam, summo favente numine, ex auctoritate magnifici rectoris D. Johannis Voet, I.U.D., eiusdemque facultatis in illustri academia Lugduno-Batava professoris ordinarii, necnon amplissimi senatus academici consensu et nobilissimae facultatis medicae decreto, pro gradu doctoratus summisque in medicina honoribus et privilegiis rite et legitime consequendis, publico examini subicit Philippus Maximilianus Helvetius, Haga-Batavus, die 1 Octobris, loco solito, a decima ad duodecimam, Leiden, Abraham Elsevier, 1686, B3v. Crit.: title Μαξιμιλιανοῦ] ΜΑΞΙΜΙΛIA´ΝΟΥ ἰατρικὴν] Ι῾ατρικὴν 1 Φίλιππε] Φιλίππε χαλινοῖς] χαλινεῖς 2 μετά μου] μετάμου 3 καπυρὰν] καπυραν || 4 Φίλιππε] Φιλίππε || 5 ἀρρήτου] ἀῤῥήτου.

- Old scientific term for tuberculosis, attested in Ancient Greek texts by authors such as Hippocrates and Galen and commonly used in similar seventeenth-century disputations.

- The expression Φύσεος ἀρρήτου καρποὺς has parallels in several early Christian writings. In this case it might have been drawn from Cyrillus of Alexandria’s de sancta trinitate dialogi, 395 d, 25, of which Bonaventura Vulcanius owned a manuscript and made a Latin translation in Leiden. Cf. De Durand, G. M. (1976). Cyrille d’Alexandrie. Dialogues sur la Trinité, Tome I. Cerf; Codex Vulcanianus 52 & 12, Leiden University Library.

- The concept of cultural capital was coined by Pierre Bourdieu and refers to non-financial assets like knowledge, skills, education, and tastes that can be used to demonstrate one’s cultural competence and social status. Cf. Bourdieu, P. (1977). Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction. In J. Karabel, & A. H. Halsey (ed.), Power and Ideology in Education, 487–511. Oxford University Press.

- A notable example is Anna Maria van Schurman, Europe’s first female university student and, with her letters in the Opuscula (Leiden, Elsevier, 1648), the only other female author of New Ancient Greek in the Low Countries we could identify so far. She was widely celebrated and honored as the tenth muse and the virginum eruditarum decus. Cf. notably the research of Pieta van Beek.

Figures

- Figure 1: Title page of Philippus Maximilianus Helvetius’ disputation on Atrophy (ustc 1836756). UBL, Special Collections, 236 C 5:33

- Figure 2: Margareta Ripen’s gratulatory poem (UBL, Special Collections, 236 C 5:33, B3v)

- Figure 3: Promotion at Leiden University, Hendrick van der Burgh, circa 1650, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

Further reading

- Ahsmann, M. J. A. M. (1990). Collegia en colleges: juridisch onderwijs aan de Leidse Universiteit 1575-1630 in het bijzonder het disputeren. Wolters-Noordhoff.

- Lamers, H. & Van Rooy, R. (2022) Graecia Belgica: Writing Ancient Greek in the early modern Low Countries. Classical Receptions Journal, 14(4), 435-462.

- Van der Woude, S. (1963) De oude Nederlandse dissertaties. Bibliotheekleven, 48, 1-14.

- Van Rooy, R. (2023). New Ancient Greek in a Neo-Latin World. Brill.

How to cite

Dries, Nijs. 2025. “A Woman Writing New Ancient Greek Poetry for a Leiden Disputation (1686).” Hermes: Platform for Early Modern Hellenism (blog). 1 December 2025.

Deposit in Knowledge Commons: https://doi.org/10.17613/5gyan-3p804