Thijs Kersten (Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen)

Writing to one of his pen pals on January 21, 1605, the Lowlandish scholar Justus Lipsius (1547–1606) could not help but address the elephant in the room. However pleasant his contact with the Spaniard Francisco Quevedo (1580–1645) had been, Lipsius felt the need to mention the wars Quevedo’s king had been waging on the Low Countries for years. First, the Guelders Wars (1502–1543) had ravaged the Low Countries, and now the Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648) followed suit. Lipsius took to the Trojan War as a frame of reference. He exclaimed “And now you happily serve Mars! […] We have become a shared grave for Europe. If only Minerva with her Odysseus would have stood next to your Agamemnon! How good would that do both you and us.” [Atque utinam felicius Marti! […] Commune sepulchrum Europae sumus. O si Agamemnoni vestro Minerua cum suo Vlysse adsistat! Vestrum et nostrum sit bonum.] Simply put, if only the Habsburg king had some wisdom, then this violence might have been avoided.

Lipsius calls the Low Countries a commune sepulchrum Europae, referencing a line from the Roman poet Catullus, who described Troy as commune sepulcrum Asiae Europaeque.[i] These references to Troy were not unique. Both upper class (humanist) and lower class popular audiences evoked the war at Troy to confront their experiences of war and suffering at the hands of the Habsburg Spanish, a process I have called associative memory elsewhere.[ii] Similarities between the destruction of the Low Countries and the Fall of Troy were expressed in Dutch, Latin, and New Ancient Greek – the latter being the rarest of the three linguistic registers. In Dutch popular songs, for instance, the Spanish sieges of Breda in 1590 and Oostende in 1604 were compared to the Trojan horse, by both locals and historians across the Low Countries.[iii]

This contribution centres around the role of Hellenism in this discourse of remembrance and resistance. Lamers (2023) recently studied the symbolic value of Ancient Greek in the Low Countries. He tentatively states that both the language and its script could evoke Dutch liberty and resistance. Detaching themselves from Latin (and its modern progeny, Spanish), the Dutch may have adopted Greek as a symbol of political liberty. This contribution aims to support Lamers’ (2023) argument and adds the dimensions of remembrance and heroic victimhood to the mix. To do so, I discuss a poetry zine from Zwolle about the Guelders Wars from 1553 as well as the largest New Ancient Greek epic of the Low Countries (1605), written to remember a siege in the Eighty Years’ War.

The Ἀληκτὼ sive somnium furoris bellici (1553)

Although vernacular media often referenced the Trojan War, such as in public theatre plays by rederijkers, in prints, or in vernacular histories, the most direct and obvious engagement with Troy occurred in humanist works. One of these is a booklet of Neo-Latin and New Ancient Greek poetry, published in Zwolle in the wake of the Guelders Wars. The booklet was produced in 1553 by Joannes Telgius, a schoolmaster born in Apeldoorn about whom little is known. He titled the work ΑΛΗΚΤΩ SIVE SOMNIVM furoris bellici, quo nunc passim mundus tumultuatur. In this multilingual title, Telgius hints at the New Ancient Greek and Neo-Latin poetry inside and introduces his topic: a dream of the rage of war that currently shook up the world, stirred by Alecto, one of three Greek furies.

It is made up of several parts, with the first part in Latin: a dedicatory letter to the youth of Zwolle (iuuentuti Suollanae; A1), an elegy by Telgius of 234 lines, a Distichon cuiusdam docti of 2 lines, a Latin-language Παρανετικὸν to the Muses of 44 lines, and a Latin EXPOSTVLATIO PESTILENTIAE or ‘Complaint about the famine’ of 46 lines. These are then followed by works in New Ancient Greek, namely a translation of the first section of Telgius’ long elegy (6 lines) and a summary of its remainder (2 lines), an ode to the youth of Zwolle (12 lines), and a ‘summary’ of a prayer to God (6 lines).

The collection was directed at the youth of Zwolle to teach them a “poem for Saint Martin” (carmen Martinianum; A1), one that should stick with them. As every student was made to buy a booklet, they could consult it as they grew up (nostram operam boni consule; A1). From its successive poems, we can gather a clear point. The youth of Zwolle were to understand the horror of war and to stop it, similar to Trojan heroes. It was 19 years later, before most of Telgius’ students had reached the age of forty, that Zwolle would be massacred by the Spanish general Don Frederik (1537–1585). Through arrangement of the poems and their development from Neo-Latin to New Ancient Greek, the booklet supports Lamers’ theory on Ancient Greek as a symbol of Dutch liberty.

Step one was to establish the scene. In the first poem, Telgius’ long Latin elegiac, he recounts the Guelders War and complains that “the golden peace has quietly left the lands it hates” (tacite exosas linquit pax aurea terras; A2, recto). The reason is simple. Charles V sought to expand his territory, moving towards France first. Telgius writes: “Don’t you see that Charles surrounds you with many kingdoms on all sides, by land, by sea?” (Nonne uides Carolum numerosis undique regnis / Cingere te terra, cingere teque mari?; A2). The war spreads across the world, with devils coming out as “incurable fury, known across this criminal world” (furor insanus, scelerato notus in orbe; A2).

Step two was to introduce Trojan heroism into the mix. Telgius does this in two steps. First, a Latin Παρανετικὸν to the Muses, anonymous but possibly written by Telgius himself tells us of past empires turned to ruin. War threats to wipe out Zwolle, as it had Rome, Alexander the Great’s empire, and Troy.

Magna fuit quondam Romanae gloria gentis,

Magna, sed è medio lenta ruina tulit.

Pellaeo iuueni, cui non suffecerat orbis,

Quid superest regis nomen inane nisi?

Somnia sunt Hector, nihil huius uictor Achilles, [...]

Once, the Roman race enjoyed great glory,

great, but a slow ruin destroyed it,

and that youngster of Pella, for whom the world did not suffice,

What is now left of this king except his hollow name?

Hector is a mere dream, his victor, Achilles, is nothing anymore [...]

In part, the poem has a didactic aim. The poet hopes to incite the youth of the city to study the arts and to realise that, even in the midst of war, learning serves its purpose. At the same time, the concurrent theme of the horrors of war and the need to respond sticks.

The final Latin poem of the collection, an equally anonymous Expostulatio Pestilentiae, or ‘Complaint by Pestilence’, returns to the horrors of war from the perspective of Pestilence itself. Among other things, the personification asks whether “the Trojans, pained by the harsh lash of a whip, did not know why they were being hurt?” [Non sapiunt Phrygii duro nisi verbere caesi / cur?]. As the poems frequently return to the Trojan War as a frame of reference for war-torn Zwolle, we reach a shift in language.

The first of the New Ancient Greek poems is a translation of the opening of the booklet made by Boetius Epo (1529–1599), a Frisian scholar with ties to the Collegium Trilingue, who was working in Zwolle at the time.[iv] His translation eases the students into the linguistic shift, by recalling the core idea that λάθρα Εἰρήνη κατελείψατο χρύσεα γαῖαν [“the golden Peace has secretly left the land”]. As the booklet itself attests, these few Greek verses were even meant to be sung by the students (decantandum pueris; A4). The following ὨΔΗ ΤΩΝ ΝΕΩΝ ΖΟΥΩΛΛΑΙΩΝ [“Ode on the Youths of Zwolle”; A5] was written by a local man with ties to humanist circles in Leuven, the humanist Stephanus Mommius, who eventually became rector in Zwolle.[v] He laments Ares and his love for strife (ἔρις) and πόλεμοί τε μάχαι τε – a reference to Iliad 5.891. Centralising the Iliad, Mommius presents the violence of the Guelders War through its similarity to the strife, wars, and battles Troy. This takes us a step further than the earlier evocations of Troy in the Latin-language poems. Ancient Greek becomes a language of remembrance, of heroism, of resistance against Habsburg Spain.

Σχέτλιε καὶ βροτολοιγὲ Ἄρες τε βιοφθόρε δαῖμον

ἀεὶ γάρ τοι ἔρις τε φίλη πόλεμοί τε μάχαι τε

καὶ μέροπας μαχέσασθαι ἐνὶ κρατερῇ ὑσμίνῃ

Merciless, plague of humans, Ares, you life-crushing demon,

strife and war and battle are forever dear to you,

as is making humans battle through powerful combat.

The final poem of the collection continues these themes. The anonymous poet, perhaps Mommius, prays to God to “stop this evil strife so that / both the old and the young people will show you more honour” [ληγέμεναι δ’ ἔριδος κακομηχάνου, ὄφρα σε μᾶλλον / τιῶσιν λάοι ἢ μὲν νεοὶ ἢε γέροντες] – adapting line 257 from book 9 of the Iliad. Noteworthy is the use of eris in both poems, an indirect, yet clear reference to the goddess Eris who was responsible for starting the Trojan War.

If we are to believe that Telgius’ students paid as much attention to his publication as he wanted them to, they picked up a message along these lines: war and suffering were imminent, learning remains a worthwhile endeavour, and look to the past for inspiration – to the Romans, to Alexander, and especially to Troy. This booklet underscores Lamers’ (2023) point, as it turns Ancient Greek into a language of anti-Spanish resistance and remembrance of Spanish violence.

The Harlemias (1605)

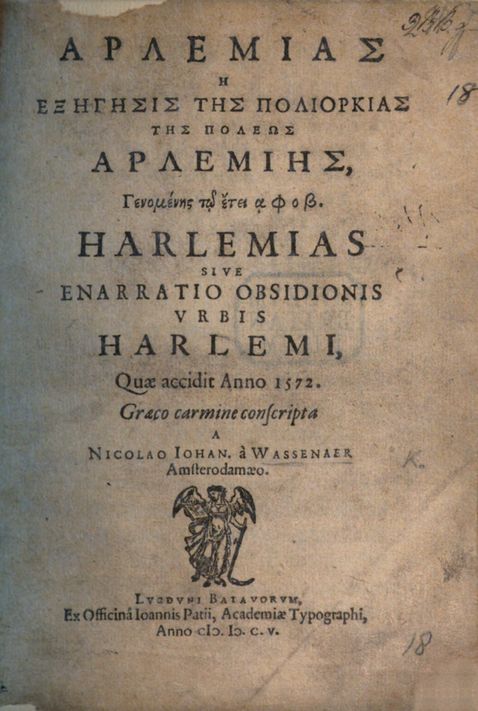

The weight of Ancient Greek as a language of liberty and anti-Spanish resistance carried more heavily in the Ἁρλεμιὰς ἢ Ἐξήγησις τῆς πολιορκίας Ἁρλεμίης, Γενομένης τῷ ἔτει ͵α φ ο β [“The Harlemias or the Story of the Siege of Haarlem, which Occurred in the year 1572”]. Written by Nicholaas van Wassenaer in 1605, it is a New Ancient Greek epic of 1462 verses paired with a Latin translation propter Tyrones, for beginners (*2 verso), one of two New Ancient Greek epics to survive from the early modern Low Countries.[vi]

Like most Neo-Latin epics, the Harlemias is a poem of praise that sought to legitimise structures of power and the local status quo. What it sought to praise was not princely power, however, but Dutch power and liberty. After 1573, Haarlem was destroyed and sunk into religious conflict. By 1605, when van Wassenaer wrote his Harlemias, Haarlem and the broader Northern Low Countries of which it was part were in need of a shared story about anti-Spanish resistance and Dutch liberty. Homeric Greek not only portrayed this heroism by its Trojan associations, but also by its symbolic power as suggested by Lamers (2023).

I note here only two small points taken from the larger work. First, just like Telgius and Mommius, Van Wassenaer does not place blame for the ongoing wars squarely with the Habsburg kings, but also directs his attention at Eris. In lines 58-60, he writes:

Ἀλλ’ οὐ τοῦτ’ Ἔριδι θρασυμηχάνῳ ἥνδανε θυμῷ,

ἐς Βασιλῆα Φίλιππον ἀπῆλθ’ ἀπατήλια βάζειν,

βασκαίνωσα ἀποστάσεως τὴν Βελγίδα γαῖαν,

But this did not please Eris, manipulative as her heart is,

and to King Philip she went to speak her wily words to him,

claiming that the Belgian land wanted to revolt.[vii]

In a continuation of the sentiments we find in Telgius’ booklet, the Eighty Years’ War, too, must start like the Trojan War had done. Haarlem seems to suffer a fate similar to what Telgius had predicted for Zwolle. Both cities fell at the hands of the Spanish general Don Frederik, whom the Harlemias calls an ἀνδροφόνος [“killer of men”].

Second, a stock phrase is sprinkled across the Harlemias to underscore why the Dutch are fighting (back) against the Spanish. This core message encapsulates the ideals of the Harlemias. It is expressed in lines 76-77, lines 80-81, lines 162-163, lines 397-398, and line 1146. To quote but one, in ll. 80-81, we hear that the Dutch are fighting:

Κάλλιστόν γε δοκεῖ Βέλγαις φρεσὶ τοῦτο, μάχεσθαι

γῆς περὶ, παίδων τε, κτεάνων τε, ἐλευθερίης τε.

For it seemed the most beautiful thing to Dutch minds to fight

for their country, their kids, their possessions, their liberty.

This summary of the aims of the Dutch shows how strong the desire for liberty was. Although the passage in itself might not prove Lamers’ point, it is part of a larger symbolic value of Greekness that he has traced in the Pleumosias and that I believe to find in the Ἀληκτὼ sive somnium furoris bellici and Harlemias. According to this preliminary reading of these two texts, I argue the symbolic charge of Ancient Greek as a language of liberty holds up.

Conclusion

While my conclusion remains as careful and tentative as the one expressed by Lamers in his 2023 paper, I hope to have shown that the symbolic status of New Ancient Greek as a language of Dutch liberty and resistance has some sturdy legs to stand on. Not only the Pleumosias, but the Ἀληκτὼ sive somnium furoris bellici and the Harlemias use New Ancient Greek in a similar fashion. Their use of the language reveals how it served to create an independent Dutch identity, a feeling of resistance, and a heroic memory of a traumatic series of wars that would last decades more. When we study these works against the backdrop of popular works that continuously reference Troy, from histories and plays to songs and paintings, we also get a better view of the position New Ancient Greek had. Although writing and reading works in New Ancient Greek was, without question, an elite commodity and certainly not accessible to the large majority of people in the Low Countries, it did not exist in a cultural vacuum.

Figures

- Figure 1. Map of the siege of Haarlem, from Braun and Hogenberg’s Civitates orbis terrarum (1575).

- Figure 2. Title page of Telgius’ Ἀληκτώ (1553).

- Figure 3. Map of the siege of Haarlem, based on a copper engraving by Antonio Lafreri (1573).

- Figure 4. Title page of Nicholaas van Wassenaer’s Ἁρλεμιάς (1605).

References

- Bleau, J. (1649) Toonneel der Steden van de Vereenighde Nederlanden, Met hare Beschrijvingen. Amsterdam.

- Boers, B. (2013) “Een 16de-eeuws schoollied uit Zwolle.” Nieuwsbrief Stichting Vrienden van het Johan van Oldenbarnevelt Gymnasium Amersfoort no. 2: 15-19.

- Duym, J. (1606) Een Ghedenck-boeck, Het welck ons Leert aen al het quaet en den grooten moetwil van de Spaingnaerden en haren aenhanck ons aen-ghedaen te ghedencken. ENDE de groote liefde ende tou vande Princen uyt den huyse van Nassau, aen ons betoont eervvelick te onthouden. Leiden.

- Kersten, T. (2023) “Een Nederlands Troje: Herdenking via homerische epiek in Nicolaas van Wassenaers’ Harlemias.” In: De kracht der herinnering, edited by M. Clement, H. Mooiman, & I. de Smalen, 156-175. Utrecht.

- Kersten, T. (under peer review) “Revisiting Multidirectional Memory: Associative Memory.” Memory Studies Review.

- Lamers, H. (2023) “A Homeric Epic for Frederick Henry of Orange: The Cultural Affordances of Ancient Greek in the Early Modern Low Countries.” Humanistica Lovaniensia 72: 323-348.

- Parrado, P.C. (2017) “Argutae et litteratae: una nueva mirada sobre el intercambio epistolar entre Francisco de Quevedo y Justo Lipsio (1604-1605).” In Quevedo en Europa, Europa en Quevedo, edited by J.S.A. Veloso, pp. 36-78. Vigo.

- Telgius, J. (1553). ΑΛΗΚΤΩ SIVE SOMNIVM furoris bellici, quo nunc passim mundus tumultuatur. Zwolle.

- Thomas, W. (2004) De Val van het Nieuwe Troje: Het Beleg van Oostende, 1601-1604. Leuven.

- van Wassenaer, N. Jnsz. (1605). ΑΡΛΕΜΙΑΣ Η ΕΞΗΓΗΣΙΣ ΤΗΣ ΠΟΛΙΟΡΚΙΑΣ ΤΗΣ ΠΟΛΕΩΣ ΑΡΛΕΜΙΗΣ, Γενομένης τῳ ἔτει ͵α φ ο β. HARLEMIAS SIVE ENNARATIO OBSIDIONIS URBIS HARLEMI, Quae accidit Anno 1572, Graeco carmine conscripta A NICOLAEO IOHAN. à WASSENAER Amsterdamaeo. Leiden.

Footnotes

[i] Lipsius’ letters to Quevedo are stored in the library of the Universiteit Leiden. They were recently made accessible by Parrado (2017). The reference to Catullus is drawn from carmen 68, line 89, where the poet curses the city for its association with death.

[ii] Kersten, under peer-review. The principles behind this theory were already expressed in Kersten 2023.

[iii] For Breda, inter alia J. Duym, Ghedenck-boeck (1606). For Oostende, inter alia J. Bleau, Toonneel der Steden (1649). Cf. Thomas 2004.

[iv] Boetius Epo (https://www.dalet.be/person/83) taught Hesiod and Homer in Leuven and also edited a book on Homer that was published in Leuven in 1555.

[v] Stephan Mommius (https://www.dalet.be/person/563) also wrote a liminarium for the Hebrew grammar of Joannes Isaac, published in 1557.

[vi] For the second, the Pleumosias, see the work by Lamers (2023). The work is currently under study by Han Lamers (Rome / Oslo) and Dries Nijs (Leuven).

[vii] The word form βασκαίνωσα is a dialectal variant of the standard (Attic) βασκαίνουσα. It illustrates how Van Wassenaer imitates the Homeric dialect. He also applies dialect forms to his neologisms, such as Βαταβοστυγέεσσιν (‘Haters of Dutchmen’) in Aeolic dialect.

How to cite

Kersten, Thijs. 2026. “Trojan Heroes of the Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648): New Ancient Greek, Liberty and Remembrance” Hermes: Platform for Early Modern Hellenism (blog). 1 February 2026.

Deposit in Knowledge Commons: https://doi.org/10.17613/hs6jt-zpy30