Chiara Gazzini (University of Oslo)

The Steigenberger Inselhotel on Lake Constance, formerly a Dominican monastery, holds a copy of an epitaph ascribed to the Italian humanist Pier Paolo Vergerio (1370–1444/45). Originally placed near the altar of the monastery, the inscription was on the gravestone of a Greek who died in Constance on 15 April 1415 during the Council, and praises him as a highly educated, wise, and honest man. The man, celebrated in a similar inscription by Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459) for his services to the homeland and for restoring the Greek language in Italy, is the Byzantine Manuel Chrysoloras.

Born in Constantinople in 1360 to a noble Byzantine family, Chrysoloras was a distinguished scholar, professor, and high-ranking diplomat in the service of Emperor Manuel II Palaeologus (1391–1425) during the years of the Ottoman threat. As an imperial ambassador, Chrysoloras made his first trip to Italy sometime between 1390 and 1395, travelling to Venice with his compatriot Demetrius Kydones (c. 1324–98). On this occasion, Chrysoloras made his first contacts with the emerging world of Humanism, giving private Greek lessons to the Florentine patrician Roberto de’ Rossi (d. 1417) and attracting the attention of Coluccio Salutati (1332–1406). As chancellor of Florence, Salutati offered Chrysoloras the newly created chair of Greek at the city’s university, where the Byzantine taught from 1397 to 1400: among his students were Pier Paolo Vergerio, Leonardo Bruni (1370–1444), Jacopo d’Angelo (c. 1360–1411), and other future leaders of Italian Humanism and translators of ancient Greek literature. Chrysoloras left Florence in 1400 to join Manuel II in Lombardy, where he spent three years until 1403, dividing his time between diplomacy, teaching, and literary pursuits. One of his students at the time was Uberto Decembrio (d. 1427), a member of the Visconti intellectual circle in Pavia; with him, Chrysoloras prepared the first Latin translation of Plato’s Republic, a crucial step in the recovery and transmission of the classical heritage to the West.

In the following years, Chrysoloras was involved in diplomatic missions on behalf of Manuel II and visited some of the Western royal courts to seek aid for his besieged homeland. For the same purpose, Chrysoloras travelled to Bologna in 1410 to meet Alexander V (Peter Philarges, c. 1339–1410) but missed the opportunity due to the antipope’s sudden death. Agreeing to join the entourage of John XXIII (Baldassarre Cossa, c. 1370–1419), Chrysoloras accompanied the new antipope on his transfer to Rome in 1411 and sojourned in the city until 1413. It was a fruitful period for Chrysoloras’ cultural endeavours, as he had no official position or duties to fulfil within the papal Curia. His pupil during those years was John XXIII’s secretary, Cencio de’ Rustici (d. 1445), who later played an important role in Roman Humanism as a discoverer of manuscripts and translator of Greek texts.

The last chapter of Chrysoloras’ life coincides with the early stages of the Council of Constance, convened by John XXIII to end the Western Schism. Chrysoloras played a part in its preparation, being one of the envoys sent by the antipope to the King Sigismund of Luxembourg (1368–1437), in 1414, but it is not clear if, or how much, he contributed to its work. Although weak and ill, in Constance Chrysoloras managed to teach Greek to Bartolomeo Aragazzi (d. 1429), another prominent Italian humanist and translator, before dying on 15 April 1415.

Among modern scholars, Chrysoloras is best remembered for his role as distinguished professor of Greek in Italy and for his pioneering contribution to the revival of Greek studies in the Renaissance. Indeed, Chrysoloras’ teaching in Florence marked a turning point in early modern cultural history, laying the foundations for a stable tradition of Greek studies in Italy and Europe. In addition, Chrysoloras’ Greek grammar, the Erotemata, served as a standard textbook for many generations to come. Later biographers hailed Chrysoloras’ coming to Florence as an epochal event, but his contemporaries did not hide their excitement either: Coluccio Salutati greeted the news of Chrysoloras’ imminent arrival as that of a new god, while Leonardo Bruni did not regret abandoning his law studies to attend Chrysoloras’ classes and learn the language that would finally enable him to “speak” with Homer, Plato, and Demosthenes. This is perfectly in keeping with the cultural climate of late fourteenth-century Florence and the trends specific to Salutati’s circle. At the same time, it reflects, at least in part, Chrysoloras’ own vision of his activity in the West. This is clear from the fortnight of Greek and Latin letters that make up the bulk of Chrysoloras’ oeuvre: especially when writing to his students, the Byzantine praises the ancients as the supreme source of intellectual nourishment and notes the importance of getting a reliable picture of their works by reading them in the original language. However, Chrysoloras attached far greater importance to his cultural endeavours, which had the same motives and aims as his diplomatic service to the imperial authority. Realising, like most contemporary Byzantines, that what was left of the Empire was doomed by the advance of the Turks, Chrysoloras’ argued in his letters that a survival of Byzantium was still possible by preserving its literary heritage. For Chrysoloras, this was both a political and civic responsibility. Writing to Manuel II, he urged him to do everything in his power to prevent the loss of the rich culture that Byzantium had inherited from the ancients, aware that this would lead to the country’s ultimate downfall. For his part, Chrysoloras contributed to the goal in many ways during his lifetime: as a diplomat, promoting reconciliation between East and West; as a teacher, passing on the legacy of Greek language and literature to the Latin-speaking world; and, finally, as an epistolographer, with letters that reveal his personality, his acquaintances, his scholarly tastes, but also his efforts to build a bridge between East and West, to re-establish in the present the intimate “communion” between the two great civilisations of the ancient world, and the strength of their common culture.

Pictures

- Florentine School (Paolo Uccello?), Portrait of Manuel Crisolora, mid-15th cent., ink on paper, 9.3 × 13.6 cm. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Cabinet des dessins, Fonds des dessins et miniatures, Inv. 9849.

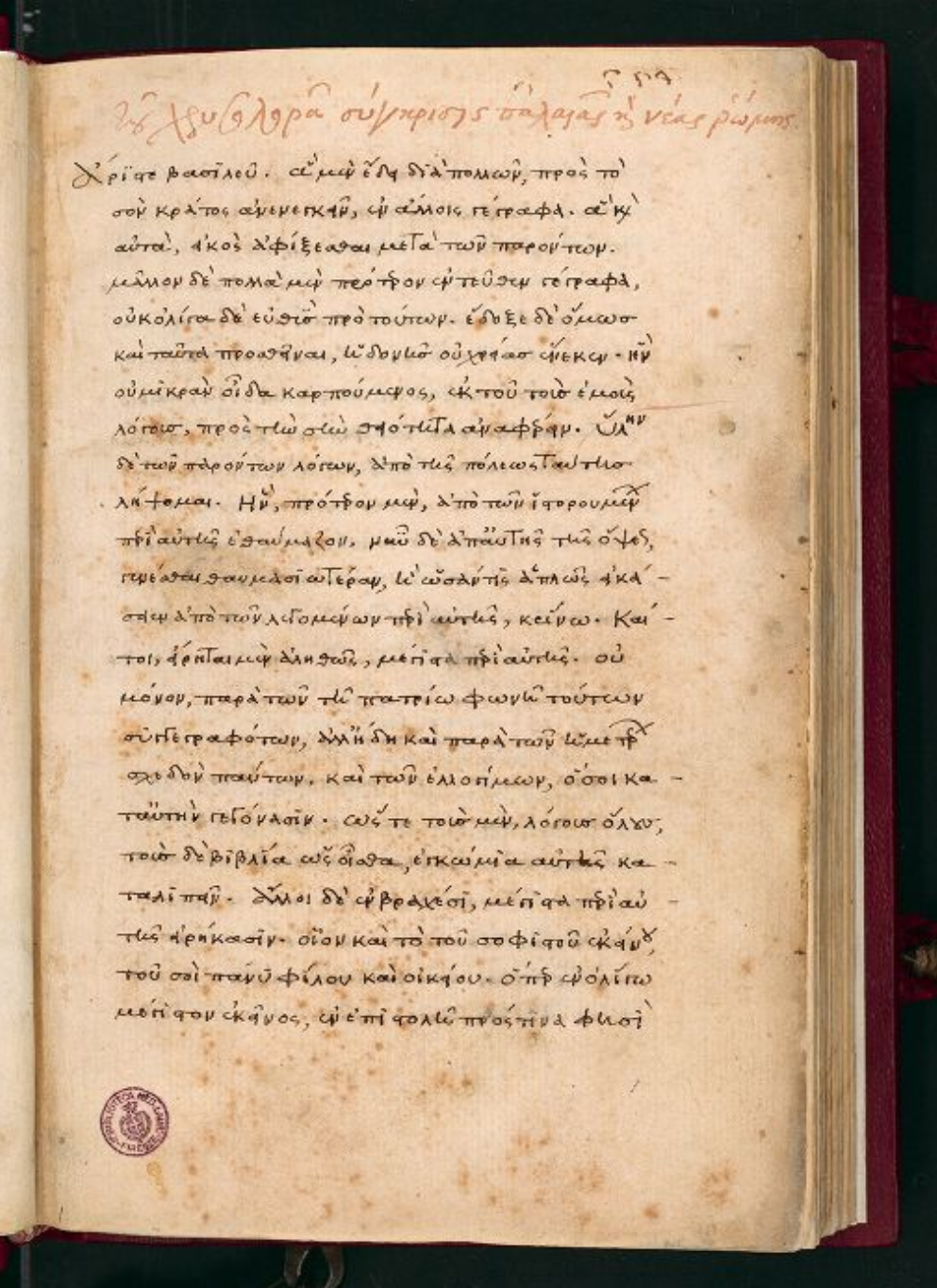

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Manuel-chrysoloras-paolo-uccello-louvre-15th.jpg (last accessed: august 2024) - Manuel Chrysoloras, Letter to Emperor Manuel II Palaeologus, Rome, June-July 1411, Manuscript copy in the author’s hand. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Plut. 6.20, fol. 1r.

Source: https://tecabml.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/plutei/id/302009/rec/1 (last accessed: august 2024)

Bibliography

- Cammelli, G. I dotti bizantini e le origini dell’Umanesimo, I: Manuele Crisolora, Firenze, Vallecchi, 1941.

- Gamillscheg, E. “Ch(rysoloras), Manuel”, Lexikon des Mittelalters, II, Stuttgart–Weimar, Metzler, 1999, 2052–53.

- Gazzini, Ch. ‘L’edizione delle epistole di Manuele Crisolora. Status quaestionis e prospettive di ricerca’, Annali dell’Istituto universitario Orientale di Napoli. Sezione filologico-letteraria 38, 2016, 119–78.

- Maisano, R. – Rollo, A. Manuele Crisolora e il ritorno del greco in occidente. Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Napoli, 26-29 giugno 1997), Napoli, Istituto Universitario Orientale, 2002.

- Mergiali-Sahas, S. “Manuel Chrysoloras (ca. 1350-1415), an Ideal Model of a Scholar-Ambassador, Byzantine Studies / Études Byzantines, n.s. 3, 1998, 1–12.

- Rollo, A. Gli Erotemata tra Crisolora e Guarino, Messina, Centro Interdipartimentale di Studi Umanistici, 2012.

- Thorn-Wickert, L. Manuel Chrysoloras (ca. 1350-1415). Eine Biographie des byzantinischen Intellektuellen vor dem Hintergrund der hellenistischen Studien in der italienischen Renaissance, Bonner romanistische Arbeiten 92, Frankfurt a.M.-Berlin etc., Peter Lang, 2006.

- Trapp, E. et al. “Χρυσολωρᾶς Μανουήλ (Chrysoloras Manuel)”, Prosopographisches Lexicon der Palaiologenzeit, XII, Wien, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1994, nr. 31165.

How to cite

Gazzini, Chiara. 2024. “At the Dawn of Early Modern Hellenism: Manuel Chrysoloras and the Revival of Greek Studies in Renaissance Europe.” Hermes: Platform for Early Modern Hellenism (blog). 1 October 2024.

Deposit in Knowledge Commons: https://doi.org/10.17613/z55a-6y21.